Maggie: Doha, Qatar

As one of 173,000 migrant domestic workers in Qatar, Maggie has always been active in the Kenyan diaspora community, and in organising her sector. The fledgling Kenyan Household Service Workers Organisation (KHSWO) is gaining momentum, and the need has never been greater. Maggie continually hears stories from migrant domestic workers who come to Qatar in the hopes of providing for family back home, but who end up being unpaid, forced to work in intolerable conditions, and who have suffered physical and sexual abuse at work (some who are permanently disabled as a result). She’s heard from women who signed contracts with sponsors through Kenyan agencies, but once in Qatar were transferred to another household for a price; effectively trafficked for profit.

During pandemic lockdowns things went from bad to worse for many of these women. Under the Kefala system (prevalent in the MENA region), sponsoring employers are officially required to provide adequate food and housing to migrant workers, but in practice there is little consequence for those who refuse to comply. During lockdown this left many migrant domestic workers trapped in their employer’s homes, starving and without hygiene supplies. Through the support of the IDWF Solidarity Fund, and local groups (which Maggie refers to as the Green Maasai Queens, and the Alkhor Ladies Fellowship), Maggie and her grassroots team have been quietly getting supplies, food and counsel to desperate workers who managed to reach out.

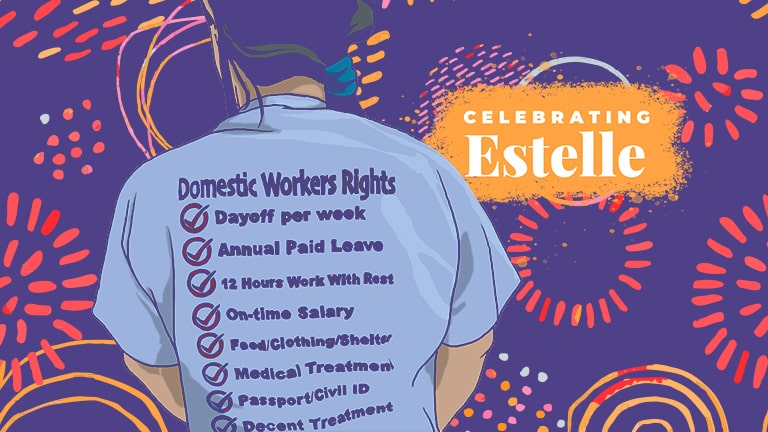

Maggie sees mobilizing and organizing as the only way to eradicate these pervasive violations of human rights. Though laws were passed in 2017 protecting the rights of migrant domestic workers in theory, in practice there is still little relief. Maggie – who took paralegal training in order to better help others to navigate the new law – has talked to women who are afraid to take legal action, both for fear of employer reprisals, and because the complaint process under the kefala system can be daunting. If you don’t have your passport and a signed contract (employers often withhold both), the process goes from daunting to near impossible. And if your employer calls the police and reports you missing (often done to avoid the consequences of a complaint), you face being jailed and deported. In Maggie’s opinion the process is biased: “The biggest problem in these situations is that where there are two opposing stories, authorities will always take the word of the employer over that of the migrant worker.”

Maggie is encouraged by the work of the IDWF in recent years – with the ILO and the Ministry of Labor –to ensure that the rights of migrant domestic workers are protected under Qatari law. Going forward, these laws will provide the KHSWO with new tools to achieve decent work for all migrant domestic workers in Qatar. “Years ago the domestic workers had no voice…but the IDWF gave us the opportunity to come together, gave us avenues to speak. The struggle will continue, but together we have power.”