Lita Anggraini is one of the most prominent activists fighting for the rights of domestic workers and women in Indonesia. She is one of the founding members of the International Domestic Workers Federation (IDWF), and the coordinator of the National Network for Domestic Worker Advocacy – Jala PRT, which currently has 35 member organizations (including 8 DWs unions representing more than 14,000 domestic workers). For more than thirty years, Lita has worked on worker education, researching the conditions of domestic workers, raising public awareness on the issues that affect them, advocating for their rights and developing strategies to change the laws so that the state recognizes, appreciates, and protects them as workers and women.

Lita and Jala PRT have played a key role in drafting and strongly promoting the Domestic Worker Protection Bill, which Indonesian President Joko Widodo aims to pass into law soon, after almost 20 years languishing in the legislature. This is a historic achievement for the domestic workers sector, a workforce composed of at least 5 million workers, of which 80 per cent are women, and 30 per cent are underage women, most of whom are breadwinners for their families.

Lita was born in 1969 in Semarang, Java. Although she grew up in an upper-middle-class family, she has always cared about impoverished and marginalized people. Her parents expected her to follow the family tradition and find a job in the civil service after graduating, but she rebelled against those plans, and left her home in 1988 to study in the Socio-Political Department of Gajah Mada University in Yogyakarta. She became deeply involved in student activism and joined a group that supported small farmers facing the loss of their land to dam projects and plantations. Working on human rights cases, Lita saw that women suffered the worst oppression, especially when they were poor or had migrated from rural areas to seek work. To shed light on this injustice, Lita and a group of friends founded the Yogyakarta Women’s Discussion Forum. The Suharto era of the late 1980s and early 1990s was a dangerous time for activists in Indonesia, and Lita faced pressure from the military for exposing cases of rights abuse, organizing demonstrations, and promoting gender equality.

Following a case of abuse and death of a young domestic worker in 1992, Lita and her friends started doing research on the domestic worker’s sector. Based on their concerning findings, they decided to focus their efforts on supporting domestic workers. Soon, Lita realized that education was essential to their empowerment, and she established a School for Domestic Workers in Yogyakarta in 2003, which later extended nationwide. Its system’s unique dual approach provides young domestic workers with the skills they need to improve their work and the tools they require to understand and lobby for their labor and human rights. At the school, women are trained in both cleaning, cooking, care-giving and other skills, and negotiating written contracts with their employers. In a country with more domestic workers than any other in the world, Lita has created a revolutionary education system that empowers young female workers to take an active role in changing their conditions and societal attitudes toward them. Her curriculum has been adopted by various government agencies as the standard for domestic workers’ education in other regions.

Domestic workers were isolated in private homes, which prevented them from socializing, seeking help or organizing. This moved Lita to set up open houses in several neighborhoods, where women workers could gather and share their experiences. Graduates of her school became leaders in these groups and founded the first domestic workers union in Indonesia: Tunas Mulia. They started promoting the use of written contracts, where terms and rights of employers and workers were clearly stated and signed. In just a few years’ time, around 300 employers were using the contract.

Lita’s innovative training program in theater, writing, and drawing spread from her school to the union, and became the basis for public awareness campaigns. Members of the union started producing a newsletter, which highlighted their writing, illustrations, and photographs. Plus, the union’s theater group has used their performances as a way to educate other domestic workers. In 2004, they successfully persuaded the Provincial Governor of Yogyakarta to issue a decree requiring the municipalities and the four regencies in that province to regulate domestic work.

At that point, Lita knew that a nationwide movement was necessary. Then, she established the National Network of Domestic Workers Advocacy (Jala PRT) to support domestic workers, as well as to advocate for regional and national policies to protect them. They have also developed a cutting-edge method of organizing women domestic workers: the “Rap” method, aimed at developing awareness of the causes and conditions of domestic worker (DW) issues while showing how a mass base organization could overcome these challenges. It provides a participatory, systematic, and dynamic process to build membership based DWs organizations, helping them to advocate for the recognition of their rights.

Soon, Jala PRT widened its scope of action at the regional and global levels, promoting the creation of the Asian Domestic Workers Network in 2005, which organized the first international meeting of domestic workers in Amsterdam (2006) with the goal of starting a global movement, and winning an ILO Convention for domestic workers. Lita also inspired domestic workers in Nepal to establish Nepal Independent Domestic Workers Union (NIDWU) in 2007. In 2009, she fostered the foundation of the International Domestic Workers Network, which in 2013 became the International Domestic Workers Federation (IDWF).

Jala PRT has been mobilizing every year on February 15, the Indonesia Domestic Workers Day. This date was set to remember the death of Sunarsih, a 14-year-old domestic worker who was killed by her employer in 2001, in the city of Surabaya. Lita’s organization has also advocated for the adoption of “pekerja rumah tangga” (domestic worker), instead of “pembantuk” (maid), as the “politics” of its name and identity has always been key to the domestic workers movement.

It was Jala PRT’s leaders who drafted the first domestic workers bill, which was submitted to the parliament in 2004 and 2009. For almost 20 years, the bill has been out of the government agenda, but Jala PRT and its members have never given up. They have made every possible effort and applied all kinds of strategies for the law to be passed. Thanks to their massive actions, campaigns, and lobby work, in alliance with migrant workers groups and national trade unions, their dream of a law for domestic workers is about to become a reality.

At least 5 million domestic workers serve as the invisible backbone of Southeast Asia’s largest economy, looking after upper-middle-class homes and freeing richer Indonesians to pursue more lucrative careers. But due to the informal nature of domestic employment, the actual number of people working in the sector is likely much higher than official statistics suggest. In any case, Indonesia is the country with the largest number of domestic workers employed worldwide.

The majority of Indonesian domestic workers are women and girls from rural areas who have very little education and often migrate to big cities searching for a job. These women and girls have grown up in a culture in which they are expected to keep quiet and accept their fate. Many people still regard domestic work –or servitude– as separate from employment. It is still largely understood as a form of loyalty to “patrons” or “superiors”. Domestic workers have consequently been marginalized, as they are looked down on as second-class citizens.

Plus, as most of them work under the live-in modality, they are physically and socially isolated, leaving them particularly vulnerable to exploitation, assault, and modern slavery.

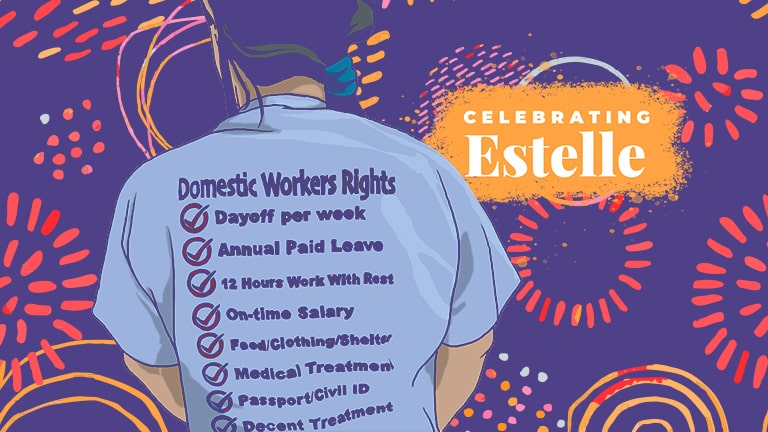

Paradoxically, the largest democracy in the world neither ratified ILO Convention 189 nor has a national law to protect domestic workers. Due to this lack of legal protection, domestic workers are employed informally without a contract, regular working hours, or provisions for maternity leave, minimum working age and wage, or social protection. The Employment Law of 2003 regulates such rights for formal workers, both for Indonesian and foreign workers, but domestic workers fall outside of this. Thus, they are susceptible to unfair treatment, including very low pay, withheld, or arbitrarily cut wages, long working hours, no regular time off, and poor living conditions.

With the promulgation of a law for the sector, the government would recognize domestic work as equal to other professions, providing domestic workers with essential benefits and rights such as health insurance, standard working hours, minimum wage, written contract, and a working-age limit. This would be a progressive move not only to deconstruct the rationale of servitude, but also to improve the social protection of domestic workers. In the absence of such legislation, thousands of women seek their fortune overseas as domestic workers. Indonesia is one of the world’s biggest sources of domestic workers, with 3.6 million of its citizens employed in wealthier homes around the world (mainly in Southeast Asia, Hong Kong, and the Middle East). The upcoming law can provide moral support to these migrant domestic workers as well as send a strong political message to migrant-receiving countries to pursue a similar policy.

Without a law, “slavery will be much more entrenched in Indonesian mindsets,” said Lita Anggraini. She sees the bill as an important protection against the idea that “anything is acceptable for a domestic worker.”