“On the International Day to Eradicate Poverty, we spoke to unionists and domestic worker leaders on their insights of how poverty affects the sector of domestic work and how women bear its disproportionate burden. Full of power, these leaders envisioned a more equitable world, with decent work for domestic workers, free of economic and gendered violence. Hear their voices!”

Details

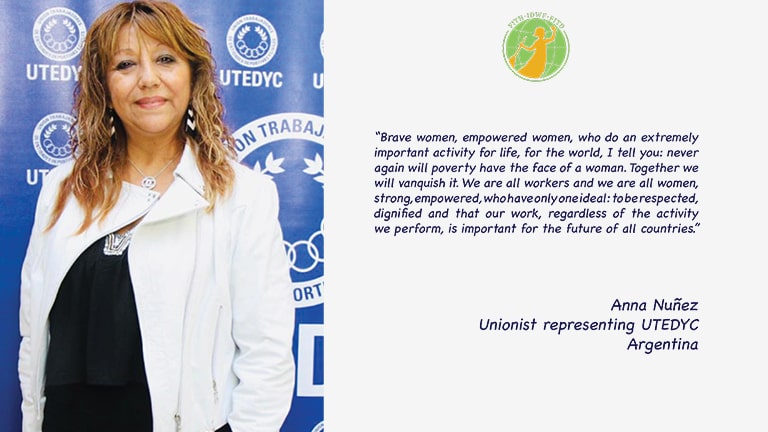

Argentina –

Ana Núñez is the Secretary of Culture and Human Rights of the Union of Workers of Sports and Civil Organizations (UWSCO) and leader of the group Mesa de Mujeres Fuerza Sindical (Women’s Union Force).

Fernanda: What is the Mesa de Mujeres Fuerza Sindical ?

Ana: It is the union of a group of women from different unions, who began to meet in the General Confederation of Labor (CGT) when I was part of its leadership. We saw that there were many women from different union sectors who did not have visibility. So, we started meeting and devising policies that specifically represent women.

With the standard political situations of unions, we, the women, saw that we were always at a disadvantage. Although we put together policies, when temporary events of a political nature occurred, we were left out, without a space. So, we began to get together at the National Women’s Institute, and something remarkably interesting happened: women from different spaces, who had not had the opportunity to meet before, came together. We made the decision to start working with a clear slogan: we were going to be a cross-cutting group working across party politics.

Why? Because the women trade unionists who are part of this Mesa speak specifically about issues that identify us, which are gender issues. From there, we designed containment policies and gave visibility to our colleagues who did not have as much visibility in their unions. Our fundamental premise is that women form part of the leadership and the decision-making. If we do not have allies in decision-making, we cannot work on topics that only women understand.

The Mesa has that spirit: we are partners in different activities, but we are united by a single premise, which is empowerment, visibility and commitment to the gender perspective.

F: Was it through the Mesa that you met Carmen Brítez, from UPACP, and contacted the domestic workers’ movement?

A: No, I met Carmen when we partook in UN Women, last year in New York. Although we both knew each other’s trajectory, we had never met in the same space. There we began to chat with Carmen and immediately we saw that sisterhood in relation to domestic workers united us, the commitment to give them visibility. We immediately considered that the accompaniment of the entire Mesa to the women domestic workers was particularly important. All women have something that unites us in domestic work. Many of us would not have been able to fulfill dreams or occupy certain spaces if we had not had the great contribution of a domestic worker in our lives. The value of these women is not visible, but it is essential. They are the ones who watch over our most precious treasures: our children and our parents. They are the ones who know the management of our houses and even act as our administrators, those who manage the household economy.

For this reason, it is extremely important that we, as women of the labor union movement, make the sector of domestic workers visible and raise awareness in other women about the fact that if they have a domestic worker in their home, they become employers. I feel part of the movement and I put at the disposal of the union of domestic workers all the support of the organization to which I belong. Many of us have done domestic work out of financial necessity, so we know very well what it means and what it means not to be valued.

F: It is essential that, even when people feel great affection for the woman who does domestic work at home, they are clear that this woman is not someone from the family, but rather a worker. And let everyone be clear that most of the women who can perform professionally, achieve it thanks to the contribution of a domestic worker at home. This shows the importance of domestic workers for the economy of a country. We must make this visible and make society aware.

A: Exactly.

Those of us who work all day often forget that a can of tomatoes is missing at home. And the domestic workers are the ones who are attending to those details. They are great economists. They must be valued, but not from compassion: “Oh, poor people, we must value them.” You must value them like any other worker because they are workers.

What happens here is that an upper-middle sector of society devalues domestic work to pay less. But I am very clear about it because I live it firsthand: in order to go to work, I need domestic workers to take care of my house, take care of my children and take care of my sick mother.

F: In these times of pandemic, domestic work is among the most vulnerable sectors. The workers are being fired, suspended, abused… And we are talking about the International Day for the Eradication of Poverty in relation to a sector mostly composed of women, and of poor women. Much is said today about the feminization of poverty. How are poverty and gender issues related?

A: When we talk about the feminization of poverty, we refer exclusively to the increase in poverty rates among women. Out of 1.3 billion poor people, more than 900 million are women. And this, in my opinion, is the consequence of gender roles: women have a stereotyped role for which we must fulfill certain functions. While this has changed a lot, it is a culture that persists. Another thing that I think also influences it, is the sexual division of labor, whereby women can only do jobs that presumably do not require strength, as if we are not prepared to do the same jobs as men. Those are guidelines that the patriarchy imposes on us, so that we can convince ourselves of them and not aspire to decent work. Another point is the difficulty that women have in accessing education, which prevents us from obtaining socially valued jobs. Women suffer historical discrimination for the mere fact of being women. This issue requires much more development, but these would be the main axes that explain the feminization of poverty.

F: In the sector of domestic work, different factors of discrimination pile-up: sex, race, poverty, ethnicity, education… It is a conventionally stigmatized and discriminated job, in which many factors combine to undermine dignity of the domestic worker.

A: As it is a job that is done indoors, in a private home, there is a favorable terrain for all these discriminations, unfortunately. When an injustice is committed against a factory worker, for example, the unions go to the door of that factory, with hype and banners, to get that worker’s rights restored. But a domestic worker must fight alone inside a house. Aside the union’s work, many times the workers are so vulnerable that they are afraid of approaching the union and losing their job for that reason. That is why the work of the International Domestic Workers Federation is so important, because the more we are, the more secure we feel. Many times it is women themselves who do not understand and are not aware: on the one hand, we fight for equality with men, but on the other we do not give ourselves the value that we have.

F: A very worrying issue for us is the extremely high level of informality that exists in the sector, so from the movement we work to reinforce the provisions of the State.

A: The State has the power to use the fundamental tool of change. The state must be committed to overseeing employers. Nobody is unaware of the situation in the domestic work sector because we are all employers. That is why I, from my place, support the struggle of the domestic workers movement and try to give them visibility. COVID-19 revealed the reality of the sector: the difference between the formal and informal workers, the situation of almost slavery to which the workers who were confined to the homes of their employers have been subjected, at risk of getting sick and without rights. I see what happens here, the reality, and it is not bad to talk about reality, because what is not said does not exist.

F: That support that you give to domestic workers and the fight for the ratification of ILO Convention 190 on Violence and Harassment in the World of Work is very important, because this Convention will complement the Domestic Workers Convention 189. If there is violence in the workplace, there is no decent work. Both conventions are interrelated and complement each other. That is why it is essential that the women’s union movement join the struggle of the domestic sector.

A: This Convention will protect women from the sectors most exposed to violence and harassment, and one of them is domestic work, due to the nature of their work “indoors”. For unions, it is difficult to enter a private home. For that reason, this convention is going to be fundamental for the sector.

F: Even for the State it is difficult to enter private homes, because an “invasion of private space” is at stake. The dilemma of the public and the private …

A: That’s right.

F: Finally, I want to ask you to say a message to domestic workers around the world, from your position as leader in Latin America for women’s rights.

A: On this very special day, from a worker to other workers: brave women, empowered women, who do an extremely important activity for life and for the world. I tell you: never again will poverty have the face of a woman. Together we will overcome it. We are all workers, and we are all women, strong, empowered. We have only one ideal: to be respected, dignified and that our work, regardless of the activity we perform, is important for the future of all countries. I hug you enormously and I hope you have been able to listen to my heart, because I spoke with it in this interview. Thank you very much.