Domestic work must not stand outside of social protection, and domestic workers’ organizing must take a seat at every negotiation table: within unionism, social dialogue, and policy making.

Details

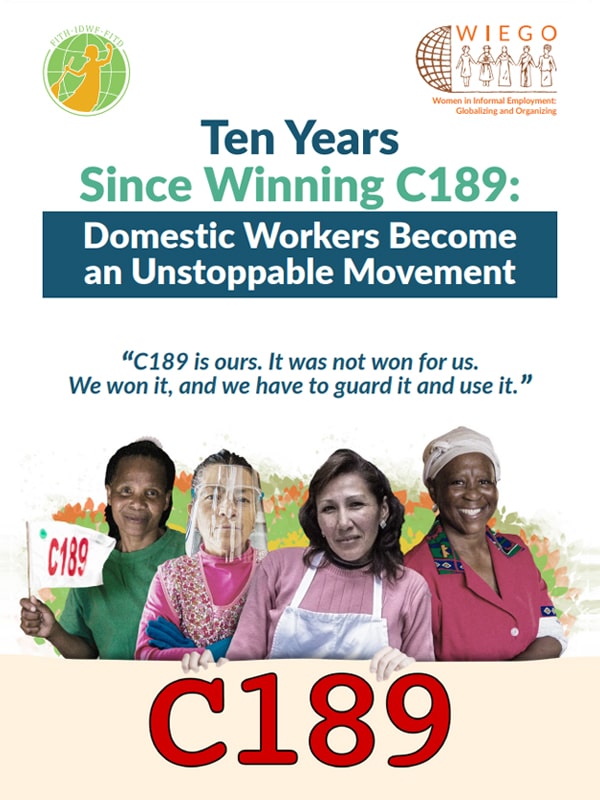

Domestic work is a historical struggle that predates the forms of organizing we see today: It is arguably not only the first form of prehistoric labor but also the first condition of life-sustenance and survival. While primordial, domestic work is inventive and imaginative: the workers have shaped a vision of justice that valorizes such labor. In doing so, it does justice to the populations engaged in it, mostly women from the Global South, BIPOC and migrant background. We are a force to be reckoned with, a force that found an echo in the anniversary we celebrate today: the 10 years since the adoption of the ILO Domestic Workers Convention 189 (C189), stipulating that domestic work is work. The IDWF, formed in 2013 represents over 590,000 domestic workers in 81 affiliates of 63 countries.

A decade on, some things have changed but many did not.

We continue to ask for decent work, a demand that is so self-evident and straight-forward yet is not achieved for many domestic workers around the world. Our sector is designated as a prototypical form of feminized labor: and as domestic workers’ labor is hidden in private households, their organizing is pushed outside of the public sphere and scrutiny, and thereby from political life. Across regions, many domestic workers, especially migrant domestic workers are prevented to form trade unions due to legal restrictions. . In many places even when domestic workers unions exist, they are continued to be ignored in the decision-making process even on matters affecting their wellbeing. Women have less resources to start with as they take on the struggles of life, and so do women workers, and women workers of feminized sectors of employment such as ours. In many regions, dominant feudal norms still reign promoting racial capitalism: instead of considering domestic work to be a profession, they consider domestic workers to be “servants” feeding off racial capitalism.

The adoption of C189 is historic, for even its most basic premise has revolutionized the prospects of domestic workers organizing. Many trade unions started accepting domestic workers in their membership as the international standard asserted that no mistake shall be made – domestic work is work. It is and remains one of our greatest victories that was both a result and an accelerator of domestic workers’ organizing. In the words of our President, Myrtle Witbooi, “C189 is ours. It was not won for us. We won it, and we have to guard it and use it.”

A decade on, a change is due!

We see disasters brought about by this vicious capitalist prioritization of profit over people. It produced COVID-19 and created the circuits for its global spread. It has fragmented health systems and denied social protections to workers. It created ecological degeneration and human commodification which go hand in hand to produce cheap labor. These are the workers on the frontlines, workers of the informal economy, domestic and care workers. Uneven development is often blamed for leaving domestic people in precarious conditions of survival. But we know the following: our exclusion is a willful act, and our inclusion shall be an act of political will as well. In the words of our General Secretary, Elizabeth Tang, “the silver lining is that we are even more convinced that a powerful global movement of domestic workers will provide us with the best protection to face any future crisis.”

With the pandemic, we hear regards for the work done, but not the workers doing it. And in this historical moment, we remind governments to ratify and implement C189, to make use of this international standard to its fullest, to abide by their legal and ethical commitment towards a sector that sustains life, and to recognize its workers.

Domestic work must not stand outside of social protection, and domestic workers’ organizing must take a seat at every negotiation table: within unionism, social dialogue, and policy making.

Download here