Over the last four years, amid highly discriminatory and oppressive labor and immigration policies, migrant domestic workers (MDWs) in Malaysia have made the unthinkable possible: they have organized collectively, built strong alliances, and put multiple strategies into practice to resist the barriers they face, gain visibility, and advocate for progressive change in their working conditions.

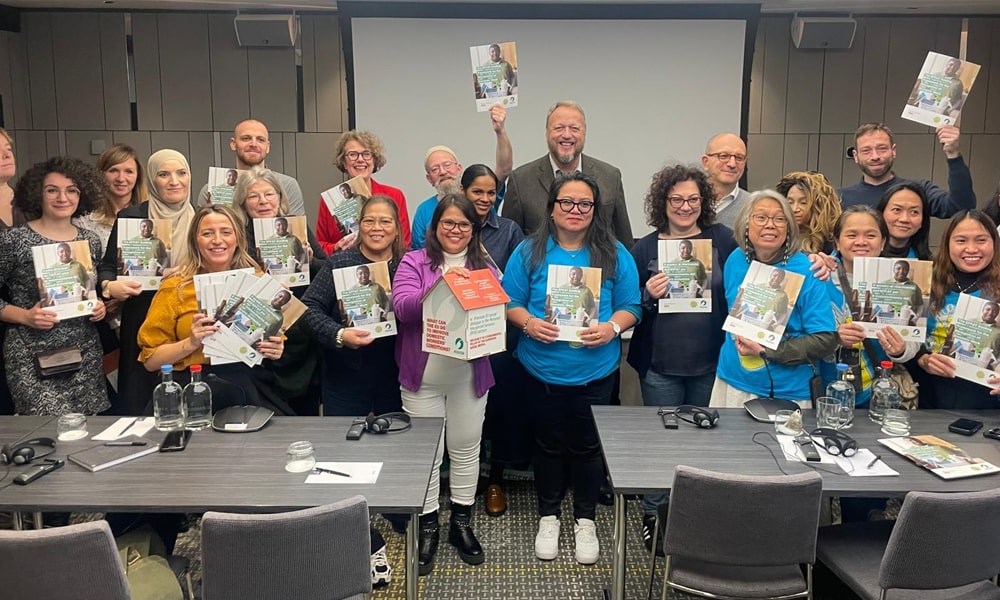

The persistent efforts of the International Domestic Workers Federation (IDWF) and its affiliates in Malaysia—AMMPO (made up of Filipina workers) and PERTIMIG (bringing together Indonesian workers)—paved the way for a substantive meeting with the Director-General of the International Labour Organization, Gilbert Houngbo, during his official visit to the country in October 2025. “It was truly inspiring to spend time with a group of migrant domestic workers here in Malaysia. They shared powerful stories about their experiences, the challenges they face, and how organizing with support of the IDWF has given them greater confidence and a stronger voice,” Houngbo said. His support is key to advancing the decent work agenda for a sector that sustains the national care economy and yet remains largely undervalued.

In Malaysia, one in five households employs a domestic worker, which indicates an estimated 300,000–400,000 domestic workers (DWs) in the country (UN Women, 2016). The disproportionately high levels of exploitation and abuse they face are a direct consequence of the lack of legal protection: the Employment Act 1955, the foundational legislation governing labor relations, excludes DWs from standard labor rights and protections afforded to other workers, such as provisions on minimum wage, working hours, weekly paid rest, public holidays and leave, overtime pay, and maternity benefits. Additionally, DWs in Malaysia face major barriers to organizing: all attempts to register DWs unions and organizations have been rejected by the authorities, which means that the rights to freedom of association and collective bargaining cannot be exercised in practice. Moreover, migration permits often impose explicit restrictions on freedom of association.

These exclusions rest on the misconception that domestic work is not “real” work but a “service” performed by women presumed to be unskilled; as a result, homes are not recognized as workplaces where an employment relationship exists and labor law applies. For MDWs, entrenched racism and xenophobia lead to even poorer working conditions and heightened exposure to abuse.

Tied to Employers, Overlooked by the State

Domestic work is the main source of employment for migrant women in Malaysia. According to the Ministry of Home Affairs, there are 129,168 registered MDWs—72% from Indonesia and 25% from the Philippines— yet the total is estimated at 200,000–300,000, as many work irregularly. Malaysian society largely depends on them to meet its growing care needs.

MDWs’ rights and conditions of employment are set out in their individual contracts and in memoranda of understanding (MOUs) signed between Malaysia and countries of origin. Malaysia’s labor-migration regulations establish that only women from an approved list of countries, aged 21–45, who have been certified as physically fit and have passed security clearance, can be employed as MDWs. In addition, workers’ nationality determines both the minimum income employers must demonstrate and the personal bond they must deposit with the Immigration Department. These gendered and racialized criteria reinforce power imbalances between MDWs and employers, as well as inequalities among MDWs of different nationalities.

While hiring a migrant domestic worker can be expensive for employers, MDWs ultimately shoulder most recruitment fees: nearly 90% pay around USD 930 to migrate. For Indonesian workers, migration costs typically amount to six to seven months’ wages. Many take out loans or become indebted to employers to cover these costs, locking them into exploitative arrangements—they cannot risk losing their job when they must repay debts and support their families. This explains why many domestic workers migrate irregularly to Malaysia.

Once employed, MDWs have limited labor-market mobility and agency. They hold a temporary work permit tied to a specific employer: they cannot change employer or job without approval from the Immigration Department and are required to live in the employer’s home. Work-permit renewal is at the employer’s discretion and also depends on the workers’ fitness for work, which must be proved by passing a medical examination and a mandatory pregnancy test. If a migrant domestic worker becomes pregnant, her contract is terminated and she is repatriated.

According to a mapping jointly conducted by the IDWF and its affiliates AMMPO and PERTIMIG (2023) among 108 MDWs and 100 employers of MDWs in Malaysia, 95% of workers surveyed had experienced being deprived of their weekly rest day, and 17% had been working for their current employer for more than two years without a day off. The findings, compiled in the report Why aren’t migrant domestic workers in Malaysia getting a day off?, also show that among those who did get at least an occasional rest day, 79% reported working an average of 4.5 hours on that “day off.” Not getting a proper rest day is detrimental to MDWs’ health: 78% said it negatively affected their mental and physical well-being.

While four-fifths of employers who completed the survey characterized their relationship with MDWs as a formal employer–employee one, many still failed to extend basic labor rights. For example, only 29% provided paid maternity leave; 32% allowed domestic workers to retain their passports; 43% allowed them to leave the house when not working; 52% allowed access to mobile phones outside work hours; and 59% provided paid sick leave. On average, workers employed by these respondents worked 13.3 hours per day. Passport confiscation not only violates rights—it also prevents MDWs from taking a day off or leaving employers’ homes, since they risk arrest if they cannot prove valid work and residence status.

Even when contracts state that MDWs are entitled to certain rights, the fact that these are not explicitly guaranteed in national legislation, combined with weak labor inspection and lax sanctions against abusive employers, leaves their working and living conditions (including wages) to employers’ discretion. This exposes them to exploitation, violence and harassment, and other rights violations—with risks especially high for those who are undocumented or in informal employment without government-approved permits. However, fear of job loss or of being reported, arrested, or deported discourages them from reporting abuse or seeking redress. An ILO study (2023) found that 29% of surveyed MDWs in Malaysia endured conditions meeting the ILO definition of forced labor.

Turning Crisis into Opportunities

In this adverse context, AMMPO and PERTIMIG developed a creative organizing model grounded in micro-level mobilization of MDWs. They began by building spaces for workers to convene and share experiences, which over time gained traction and visibility. Just as both organizations were expanding, the COVID-19 pandemic hit, threatening to roll back their efforts. Yet what seemed like a setback opened a window of opportunity, as reflected in DAWN’s recently launched book Pandemic Policies and Resistance: Southern Feminist Critiques in Times of COVID-19, which includes contributions from the IDWF and its affiliates in Malaysia.

In Malaysia, the effects of the pandemic were exacerbated by anti-migrant response policies, such as large-scale arrests and deportations of undocumented migrants, stricter enforcement of immigration laws, and the exclusion of migrant workers from emergency aid. MDWs were disproportionately affected: heightened discrimination and stigmatization as “virus spreaders”; significant loss of jobs and income (reducing remittances); heavier workloads and exhausting hours; increased occupational safety and health (OSH) risks; confinement and tightened employer control; restrictions on movement, criminalization, and arbitrary detentions.

Unable to meet in person, AMMPO and PERTIMIG began conducting virtual gatherings for MDWs and strengthened their social-media presence, creating safe spaces for sharing and connection. This new mode of interaction produced unexpectedly positive results, starting with a wider reach across the country—both to raise awareness of rights and to reinforce collective solidarity. With support from the IDWF Solidarity Fund, they set up a hotline to coordinate food-aid distribution. Each delivery included leaflets about MDW rights and PERTIMIG activities, inviting recipients to join a WhatsApp group.

The virtual format also acted as an equalizer between MDW organizations and other labor-migration stakeholders. They began regular online meetings with civil-society coalitions advancing the rights of domestic workers and migrant workers in Malaysia. This enabled MDWs to become familiar with the language of workers’ rights, collective organizing, and labor solidarity, and to build strong support networks.

This process led to the development of collective leadership of MDWs in the country. For example, AMMPO expanded its organizing to Penang. PERTIMIG, established in December 2019 with thirty members, grew to over 130 active members during the pandemic. In June 2021, PERTIMIG hosted its first founding congress (online) to adopt a leadership structure and a constitution.

In a short time, MDWs gained self-representation in different policy-making spaces, where they were invited to contribute perspectives and set priorities. Exchanges with embassies of countries of origin and representatives of the Malaysian government became a regular practice. MDW organizations also saw the opportunity to use the media as an ally, quickly gaining visibility in national mainstream outlets on issues such as OSH risks during the pandemic, the consequent need for social-security coverage, and the denial of weekly rest days.

Tangible Wins and a Path Forward

Coordinated efforts delivered tangible outcomes. In June 2021, MDWs became entitled to coverage under the Employment Injury Scheme, a branch of social security that provides compensation for accidents and/or occupational diseases arising out of and in the course of employment. In July 2024, coverage under the Invalidity and Survivors’ Scheme was extended to MDWs. In 2022, AMMPO and PERTIMIG also secured an amendment to the Employment Act, so that domestic workers are now referred to as “domestic employees” rather than “domestic servants.”

Recent support from the ILO Director-General, ongoing dialogue with the Malaysian government, and the Ministry of Human Resources’ promise to guarantee paid days off, enact protective legislation, and fully include MDWs under the Social Security Protection Scheme all show that when domestic workers adopt innovative strategies, organize collectively, and mobilize around clear goals, change is possible—even in adverse contexts with significant structural barriers. Resilience, determination, and creativity: the powerful formula that has enabled migrant domestic workers in Malaysia to turn crisis into an opportunity for progressive transformation.